Wafting through thick clouds, the silvery moon beamed down upon the throngs of people bustling along Shijō Street, Kyoto’s main commercial avenue. Although it was still only early evening, massive crowds packed the avenues, filing in and out of shops, hordes of men gravitating toward the red light districts. For generations, civil war had raged throughout Japan, and the capital had been the scene of more than its fair share of bloodshed and destruction. Months ago, one of the preeminent warlords in the country, Tokugawa Ieyasu, had defeated his main rival at the Battle of Sekigahara, and while some hoped this would finally mean an end to conflict and the establishment of peace, many remained uncertain that such peace would last. Simultaneously longing for tranquility and anxious of resurgent violence, the city’s heart pulsed. Its residents were caught up in the pleasures of the moment, as no one knew what tomorrow would bring.

gravitating toward the red light districts. For generations, civil war had raged throughout Japan, and the capital had been the scene of more than its fair share of bloodshed and destruction. Months ago, one of the preeminent warlords in the country, Tokugawa Ieyasu, had defeated his main rival at the Battle of Sekigahara, and while some hoped this would finally mean an end to conflict and the establishment of peace, many remained uncertain that such peace would last. Simultaneously longing for tranquility and anxious of resurgent violence, the city’s heart pulsed. Its residents were caught up in the pleasures of the moment, as no one knew what tomorrow would bring.

Susumu, who was propelling his way through the masses, had no time for leisure. A man of modest means, he could rarely afford to fritter away his meager income on distractions, especially with a pregnant wife at home. Normally this hour would find him at home, but his beloved Narumi had come down with a severe fever overnight. The local physician had diagnosed the illness, but lacked the remedy. Speeded by love for Narumi and the unborn child inside her, Susumu had rushed from store to store, just as they were closing for the day. After several unsuccessful attempts, he had found the cure, and while it had cost him a considerable sum, his only worry was getting it to Narumi as soon as possible.

The multitude on the main streets was making travel difficult, however, and Susumu could feel his frustration building. When a hideous woman with a coat of white powder on her face grabbed him by his sleeve, luridly offering him her services, he pulled away and ducked down an empty alley. Growing up, he had known the center of the city intimately, but since moving to the outskirts over five years ago, his memory of landmarks and shortcuts had faded. Still, he thought he recognized where he was, and as imperfect as his recollections were, sticking to the main streets entailed only more delay. He cursed as his feet struck unseen objects leaning against the plaster walls on either side of him, but he kept moving forward. When he reached the end of the alley, he swung left onto another busy road. Pushing past a group of drunken ronin, samurai who served no master, he recognized another back street, and hurried down it, fingers still white-knuckled around his medicine pouch.

One of the ronin called after him, berating him for his rudeness. Susumu ignored the harsh words and strode on. The city had seen a glut of these useless, unemployed, and often vicious warriors in the aftermath of Sekigahara. After his victory, Tokugawa Ieyasu had reduced or confiscated the lands of lords who had opposed him, and many (or all) the samurai serving those lords suddenly found themselves cast off without support, purpose or direction. When the country had been at war, it had been easy enough for a samurai to find work, as capable commanders, administrators, and strategists were always needed. Peace, however precarious, rendered those positions unnecessary. Once part of a privileged and often haughty class, the ronin demonstrated no caste was above humility–and, sometimes, even humiliation.

Despite their downfall, Susumu felt no sympathy for the ronin and had little love for the samurai in general. Even the hungriest and shabbiest among them still behaved as social superiors to the wealthiest merchants and the most skilled artisans, which was their entitlement. No member of the martial caste hung his head or offered apology for the incessant murder, arson, and forceful appropriation Kyoto (much less the country at large) had been witness to for over a century. Although there was a natural order to the world that Susumu understood, he also knew no one was more responsible for the strife and suffering that filled the recent past than the samurai.

Sprinting through the shadows, Susumu stayed focused on his mission. Soon the streets grew vacant, making his heavy breathing and footsteps the only sounds. He took this to mean he was reaching the edge of the city and quickened his pace. After a few more twists and turns, however, he found himself staring at a dead end, a high wooden gate barring his way. Grumbling, he followed the wall along the gate until the end of the block and crossed the street, but again there was no route between the buildings. He finally came to an intersection with a signpost pointing in the direction he had come.

He cursed at his foul luck. He would have to double back! It couldn’t be helped. He let out a sigh and was about to turn around when he heard steps coming up from behind. He had not seen or heard anyone for a while and an inexplicable chill iced down his spine. He began to move at a casual pace, as if by being as unobtrusive as possible he would meld into the night.

“Hold on a minute!”

In spite of his rising panic, the commanding voice forced him to halt. A breath paused in his throat. He slowly craned his neck over his shoulder as he calculated the surest means of escape. He suspected they were a bang of common criminals, moving in on solitary prey. Susumu had no intention of parting with what little money he had if he could help it.

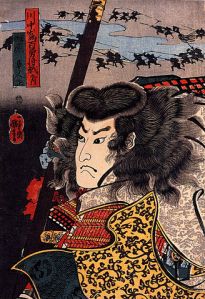

Yet he quickly saw that these were no simple thieves. They were five men, all dressed in flashy fine quality kimonos of various colors, some with their shoulders covered by much larger women’s kimonos decorated with floral or animal patterns. Each wore their unkempt hair free and messy, cascading down their necks and backs. At their waist, they wore the double swords distinctive of the samurai: the katana and its slightly smaller companion, the wakizashi. No words passed between them as they moved sideways, eyes fixed on Susumu. They were fanning out, surrounding him on either side. He could smell malice on the air even if they had not yet drawn their blades. There was no mistaking they were out for blood.

One man stepped forward from the rest. He looked much younger than the others, his cheeks untouched by stubble.  Thin, sleepy eyes peeked out from beneath strands of silky blackness, sizing up Susumu like a piece of meat. Without a change in countenance, he used his left hand to pull the sheath of his katana forward, the moon glimmering against the black lacquer finish. With his other hand, long delicate fingers curled around the grip of the hilt. His right shoulder dropped suddenly as his steps became longer and longer.

Thin, sleepy eyes peeked out from beneath strands of silky blackness, sizing up Susumu like a piece of meat. Without a change in countenance, he used his left hand to pull the sheath of his katana forward, the moon glimmering against the black lacquer finish. With his other hand, long delicate fingers curled around the grip of the hilt. His right shoulder dropped suddenly as his steps became longer and longer.

Susumu had spun around and was running long before the steel left its scabbard. Dizzy with panic, he almost tripped over his own feet as he dashed up the road, where he saw lamps burning behind curtains. He tried to call for help but the discordant noises that emerged from his mouth contained nothing coherent, only raw terror. His hands seeped with sweat and he could feel the medicine in his grasp coming loose. He ran on and on, not daring to look behind him.

He felt the warmth and the wetness before he felt the pain. It was if someone had poured hot oil down the collar of his kimono, soaking it. Then someone set it on fire. The searing agony roared through him, sending him into convulsions. The ground beneath his feet vanished, then came crashing up to meet him as his face collided with dirt and dust. He lay on his stomach as a cold breeze blew over the diagonal cut the sword had made across his back, from his neck to his buttocks. He screamed and screamed until he breathed no more.

—

Daisuke watched uneasily as the man before him, hands shaking, poured himself some more sake. Although the pair were drinking in a humble brewery in one of Kyoto’s seedier districts, it was still a major faux pas for a person to refill his own cup. It was becoming readily apparent that Daisuke had made a serious error in his judgment.

“How long did you say you had been traveling?”

“I would reckon five or six years,” slurred Daisuke’s guest, a ronin named Ishikawa Genpachi. He took a long sip and then smacked his lips with appreciation for the warm, intoxicating liquid. Beneath his heavy beard the samurai’s cheeks shined red with inebriation.

“And in that time, which masters have you studied under?”

Genpachi paused a moment and cleared his throat, obviously buying time. He kept his eyes down as he rattled off names. “Yamada Ryushin, Okuyama Chikuzen, and Usami Kogetsu.”

Daisuke tapped his chin. “I’ve never heard of any of those swordsmen…”

“They’ve never heard of you either!” Genpachi snapped, suddenly flush with anger. He tugged at the two swords tucked in his sash. “What would someone like you know about the Way of the Sword?”

Holding up his hands in a conciliatory gesture, Daisuke grinned wide. “Of course, you’re right, Ishikawa-dono. I meant no offense by my ignorance. Please, relax and enjoy yourself.”

Seemingly soothed, the drunken samurai picked up his cup and slouched forward. He acted as though the whole world weighed down on him, but he showed no sign of gratitude for the stream of liquor Daisuke was supplying him with. Indeed, since Daisuke had approached him on the street and invited him into the brewery for a round or two, the samurai had yet to speak a word of thanks. Eager to accept charity but also too proud to acknowledge it, he represented the worst contradictions of the ronin. Daisuke realized now he had picked another flawed candidate.

It had been seven days since his master had sent Daisuke on his covert task, and seven days had passed without success. He had initially been optimistic that finding a swordsman of some skill would be easy enough, given the abundance of begging samurai roaming the city like wild dogs. He had clearly underestimated how difficult it would be to sort through the dregs. Most of those he interviewed had erased whatever knowledge of the sword they once had with alcohol, while a majority of those still in possession of their faculties seemed too arrogant, too meek, or otherwise uninterested in whatever someone of a lower rank had to say. Moreover, he could not settle for just anyone; he could not bring a candidate before his master unless he was absolutely confident the warrior had all the qualities his master needed. His master trusted Daisuke’s judgment and he did not want to squander that trust by bringing forward an unworthy selection.

of begging samurai roaming the city like wild dogs. He had clearly underestimated how difficult it would be to sort through the dregs. Most of those he interviewed had erased whatever knowledge of the sword they once had with alcohol, while a majority of those still in possession of their faculties seemed too arrogant, too meek, or otherwise uninterested in whatever someone of a lower rank had to say. Moreover, he could not settle for just anyone; he could not bring a candidate before his master unless he was absolutely confident the warrior had all the qualities his master needed. His master trusted Daisuke’s judgment and he did not want to squander that trust by bringing forward an unworthy selection.

Producing a pouch filled with currency, Daisuke counted out the cost of the drinks and plopped them on the table. He stood and bowed to Genpachi, careful to show the proper subservience a commoner owed one of his betters. “Thank you so much for deigning to sit and drink with me, Ishikawa-dono. I appreciated your company.”

Shocked by the abrupt end to their drinking session, Genpachi stood as well, or attempted to. Like a tree branch jostled by the wind, he swayed left and right before he caught the table to steady himself. In the process, however, the jar of sake fell and shattered, shards of ceramic spilling everywhere, the earth soaking up the lost spirit.

“Please take care,” Daisuke said, more concerned about the sharp fragments on the ground than the condition of Genpachi.

“Why are you in such a hurry?” Genpachi asked, taking Daisuke by the sleeve. Suddenly he was all smiles and laughter. “Come, sit down with me. I’ll tell you more about my adventures as a wandering swordsman. There’s no sense in letting this sake go to waste…!”

“The sake is already gone,” Daisuke pointed out, surprised by the level of obliviousness Genpachi had reached.

“We can purchase some more,” Genpachi said, by which he meant Daisuke could. “Please, sit down! We’ll call over the brewer to bring us some more. Hey, brewer! Hey, brewer!”

The brewer was nowhere to be seen. Daisuke wagered the modest old man who ran the establishment had no doubt decided to keep to one of the back rooms until the armed and volatile samurai had his fill and left. Rather than being discouraged by the lack of service, however, Genpachi just raised his voice more and began beating the table with his fist.

A voice came from the door. “Tsk, tsk. I heard this was a nice place to drink, but I suppose I heard wrong. Drinking here would only give me a headache.”

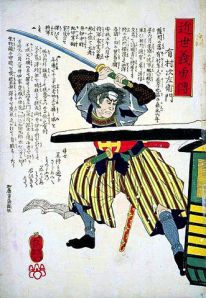

A bushy-haired samurai with thick sideburns stood at the entrance. One hand held open the curtain that hung over the doorway while the other hung limply over his swords. His tattered kimono, the color of umber, matched the hue of his skin, which the sun had thoroughly leathered. He carried himself with confidence, but not hubris. Daisuke followed the new arrival’s eyes to the spilled sake.

“What concern is it of yours?” barked Genpachi, good humor leaving him again. “This is a private gathering.”

“Don’t worry,” the bushy-haired samurai said as he strolled in. “I won’t be staying.” He made his way across the room and then disappeared down a hallway. He returned moments later, carrying a jar of sake by his side. “Have either of you seen the owner? I’d like to pay for this.”

“I believe he is somewhere back there,” Daisuke said timidly.

“Oh? Don’t tell me this idiot scared him off.”

Genpachi’s jaw dropped several centimeters.

“Being an obnoxious drunk and wasting sake are both dishonorable acts,” the bushy-haired samurai said tiredly. “But getting in the way of my drinking is the worst crime of all.”

Daisuke read the situation immediately and took two steps toward the door.

Genpachi, fuming, reached for his weapon, but by the time he was ready to use it the bushy-haired samurai had set his sake jar down and drawn his own weapon. Lunging forward, he made a horizontal slash that set Genpachi on his heels. Genpachi clasped a hand to his neck, checking to see if his throat had been slit. Yet his palm came away clean. He glanced at something tubular and hairy rolling on the floor that resembled a tea whisk. His eyes widened as he realized what it was. It was his topknot, a symbol of his status as a samurai, cut and cast from the top of his head. He choked on curses caught in his mouth, thoroughly overcome at the extraordinary speed he had witnessed and the terrible disgrace done to him. More out of embarrassment than sense he staggered hurriedly towards the exit and left.

Daisuke too was stunned. Not only had the bushy-haired samurai demonstrated his skill with the sword, but his choice to spare Genpachi’s life suggested a self-control and integrity he had been looking for, but had so far found wanting. While there was no difficulty in finding two warriors in the capital willing to fight over something as mundane as sake, it was exceedingly rare to find one that would show restraint and precision over extravagance and overindulgence. This was a man who acknowledged fate had robbed him of some of his dignity, but who also knew he possessed the means to retain some of it even in a squalid state.

The bushy-haired samurai had sheathed his katana, picked up the sake jar and had almost reached the door when Daisuke deftly stepped in front of him, eliciting a curious expression.

“Sir, please forgive me, but I was wondering if I could speak to you for a moment.”

The bushy-haired samurai looked him over. “What do you want from me?”

“I have been searching for someone like you… I need your services, sir.”

“Oh? What is it? Is your village being attacked by bandits?”

Commoner though he was, Daisuke was rankled by the question. He carried himself as the relatively affluent city dweller he was, not some country yokel. “No, sir. My master wants to hire an individual with your abilities for some discrete work.”

“Is he looking for a bodyguard?”

Daisuke smiled knowingly. “No, sir. Quite the opposite, in fact.”

Nodding, the bushy-haired samurai took his meaning. “My name is Nagai Ryōichi,” a flicker of interest lightening up his features. “I am listening.”

—

The ronin who called himself Nagai Ryōichi waited patiently for his audience with Daisuke’s master. Daisuke had taken him straight from the brewery to a well-to-do neighborhood favored by the financial elites of Kyoto, where the major dealers and traders kept their residences. The home they entered smelt strongly of burning incense, making the somber mood of the place even more acute. After removing his sandals and swords, Ryōichi followed Daisuke down a long, narrow corridor to a room decorated with paintings of chrysanthemums on the walls and sliding panels. The samurai sat on his haunches upon the wooden planks that lined the floor as Daisuke left to tell his master about his guest.

Daisuke soon reappeared and knelt by the side of the panel he had slid open. A balding, barrel-chested man approaching middle age appeared, clothed all in white. It was evident he had not shaved or trimmed his receding hair in some time. Anyone would have identified him as being in mourning for a recently deceased family member. With downcast eyes and deliberate movement, he sat down opposite Ryōichi and folded his hands in front of him.

Daisuke soon reappeared and knelt by the side of the panel he had slid open. A balding, barrel-chested man approaching middle age appeared, clothed all in white. It was evident he had not shaved or trimmed his receding hair in some time. Anyone would have identified him as being in mourning for a recently deceased family member. With downcast eyes and deliberate movement, he sat down opposite Ryōichi and folded his hands in front of him.

“Nagai-dono,” the balding man said, “I beg your forgiveness for bringing you into a home polluted by the stain of death.”

Ryōichi suppressed a sardonic laugh. “Like most of my kind, the stench of death has followed me for quite some time.”

The balding man gave Daisuke a confused look before returning his attention to the samurai in rags. “Daisuke has brought to my attention your willingness to entertain a potential job offer that requires no small amount of finesse, prudence, and care. Before we proceed, I think that I should be clear: I would like to hire you to kill someone.”

Ryōichi nodded. “Your man implied as much when he approached me. Considering the neighborhood we are in, the smell of incense, and the way you are dressed, am I correct in guessing that you are a wealthy merchant seeking someone to avenge the death of a relative?”

Flashing half a smile, the balding man nodded his head. “You have it exactly, Nagai-dono.”

“You have my deepest condolences.”

The mourner bowed his head in acceptance of these words while Ryōichi drilled his thick eyebrows together in thought before speaking aloud. “All that was simple to deduce. But if you want me to kill someone, then you must know who it is that killed your relative. If you know that, why not go to the magistrate? He wouldn’t ignore a rich man like you.”

The balding man sighed heavily, releasing repressed fury as he exhaled. “The police are not ignoring me. The truth is that they cannot do anything because, legally, no crime occurred.”

“A case of kirisute-gomen,” said Ryōichi. “Of course.”

“This was not just kirisute-gomen,” the balding man replied. “This was tsujigiri.”

Since time immemorial, samurai enjoyed the right of kirisute-gomen: to freely kill any member of the lower classes, from the lowliest leatherworker to the most famous craftsman in Japan. Ostensibly, the honorable members of the samurai class would only kill a commoner if he or she warranted it by behaving disrespectfully, but the reality was that samurai often abused kirisute-gomen when it pleased them. In these days of peace, it was not unheard of for bored, puffed-up samurai to wait at a quiet crossroads and cut down the first peasant to pass by, sometimes to test a new sword or to try out a new swordsmanship style, or even for no reason at all. This was known as tsujigiri, and while it rightly flared tempers throughout society, the relatives of those killed had no option for legal recourse or even financial compensation.

“Who was killed?” Ryōichi asked.

“My son, Susumu,” the balding man said flatly. “We were… estranged. All my life I have known only competition and the pursuit of profit. A person does not get ahead in trade unless they are prepared to sacrifice what they already have in order to obtain more.” Buddhist prayer beads clicked between his fingers. “I never should have tried to be a father. Some people just aren’t meant to raise children. When he was old enough, Susumu left this house and moved to the edges of the capital. He made and sold straw hats. I thought he was a fool to choose poverty, the very existence I clawed my way up from. But he never asked me for money. When I asked after him people told me he was happy.”

“He was killed in the outskirts of the city?”

“No. He only came into the capital to buy a medicine he couldn’t get elsewhere. His wife was pregnant and gravely ill… When he never returned, she died, along with my unborn grandson.” The balding man, struggling to keep his emotions in check, balled his hands into fists and took several deep breaths.

“How do you know who killed him?”

“The authorities found his body in a place where several peasants had been killed, all instances of tsujigiri committed by the same pack of dogs. Locals know to avoid the area because they will be murdered with impunity, but Susumu didn’t know…”

“Are they ronin who do it?”

The balding man shook his head. “No. One of the deputies charged with keeping an eye on the Imperial Court, Hakkaku Gen’ichirō, has three sons. The third is named Mitsuo, and he’s an insufferable braggart and troublemaker. He shows neither reverence nor respect for anything, yet his father’s position in the government protects him. He and his friends are the worst kind of samurai: kabukimono!”

The kabukimono were a relatively new phenomenon in the capital. Whereas samurai had once made names for themselves through acts of martial valor, some had taken to attracting attention with outrageous behavior, such as wearing their hair long and undone, singing and brawling in the streets, and so on. It did not seem to bother them that their deeds reaped infamy rather than fame, perhaps because being known as hooligans surpassed not being known at all. They were warriors in a world without war, so they went to war against the world. They were by far the most common practitioners of tsujigiri.

“Hakkaku Mitsuo thinks he cannot be touched, least of all by a commoner like me,” the balding man said. “He may be above the law, but he is not beyond your blade.”

“Why hire me? Why not hire a professional assassin?”

“I cannot risk this being traced back to me. If the son of a government official is killed, even a minor one, the investigation will be exhaustive, and I cannot risk using one of their usual suspects. Kyoto, however, is overflowing with ronin, and if Mitsuo and his gang were to encounter one in the street and a fight were to break out… Well, that would be far less strange than Mitsuo being poisoned or stabbed in his sleep.” The balding man inclined his head in a show of deference. “Nagai-dono, although you are a samurai yourself, Mitsuo and his gang are a disgrace to your class. My reasons for wanting vengeance may be selfish, but no one can dispute that their repeated practice of tsujigiri deserves a righteous punishment!”

Ryōichi held up a hand. “There is no need for fancy words. My price is 20 gold coins.”

The balding man bristled. Daisuke gasped audibly. While Ryōichi had shown a suspension of morals by allowing commoners to enlist him in assassinating another samurai, his naming his own price bluntly crossed over into the vulgar. Was this a ronin’s coarseness or the crass act of an overconfident and shameless fool? Daisuke wondered if he had not erred after all in the man he had chosen.

After hesitating, the balding man collected himself. “You will be paid after the fact, of course.”

“Of course.” Ryōichi made as if to stand, but the balding man stopped him.

“Nagai-dono, before you leave,” he said, “would you please tell me a bit about yourself? Forgive me, but I feel as though I should know more about the man I am entrusting with this serious task. Pray tell, have you been without a master long?”

“Since Sekigahara.”

“Is that so? And which lord did you serve under?”

“One of the losers.” Grinning, Ryōichi rose to his feet. “Pardon me if I don’t share my story with you. Your man has seen what I am capable of and my word is my bond. As long as you pay me, you need not worry about anything else. Hakkaku Mitsuo is a dead man.”

—

Stalking the streets like stray dogs in search of scraps, Hakkaku Mitsuo and two of his companions rambled through a run-down quarter of Kyoto. It had been almost a month since Mitsuo had cut down his last peasant (some dirty bumpkin who had met his death like a coward, screaming until he passed out) and, having just gotten his sword sharpened, he reasoned it time to once more test the blade. He had announced his intentions to his comrades before leaving their favorite brothel, and he had managed to tempt two of them away from the seductive qualities of the eager whores. Like Mitsuo, they loved playing with swords even more than they loved playing with women.

They walked along the street to an intersection where they enjoyed laying in wait for their victims. They favored this locale for its usual isolation, but tonight they spotted two men speaking in hushed tones in the center of the crossroads. The two unknown men cut short their conversation as Mitsuo and his friends approached and one began walking in their direction. Although it was poorly lit, they could see by the light of the moon that the man heading toward them carried the two swords of a samurai. Disturbed at seeing such a man here, Mitsuo’s friends slowed their gaits, but Mitsuo went on unperturbed.

“Watch this,” Mitsuo whispered over his shoulder, the edges of his lips curling.

Suddenly, Mitsuo picked up speed and, quite deliberately, brushed up against the unknown samurai, who was clearly caught off-guard. “Hey!” Mitsuo shouted, his voice so loud as to part the darkness around them. “You bastard! Watch where you’re going!”

The other samurai, who had bushy hair and thick sideburns, arched his eyebrows. “You bumped into me,” he said coolly.

“No, you walked right into me,” Mitsuo argued, “and the scabbard of your katana struck mine! Even a filthy ronin like you should know better than to be so reckless.”

The bushy-haired samurai’s face erupted with mirth. “You must be Hakkaku Mitsuo.”

Mitsuo, taken aback at hearing his name uttered by a total stranger, wavered, but kept his braggadocio going. “So you’ve heard of me! If so, you should know that I’m quite the swordsman. It’s unfortunate that you decided to cross paths with me and act so rudely.”

“I’ve heard you’ve killed many men,” the bushy-haired samurai said. “Or, to put it more accurately, you’ve slaughtered many unarmed peasants.”

Furrowing his brow, Mitsuo grabbed the handle of his sword. “What is the life of a common man to a warrior? I have a right to kill a peasant if I want, and as many as I want!”

The bushy-haired samurai nodded. “That’s true. A person’s name and status can get them many things in this world. But, these days, there is very little money cannot get you, too.”

Mitsuo’s companions drew their swords, followed by Mitsuo. Stepping back, the bushy-haired samurai drew his as well.

“My name is Nagai Ryōichi,” the bushy-haired samurai said. “You should know that I have been hired to kill you.”

Mitsuo let out a roar of laughter and lifted his katana above his head. He charged blindly, his blade dropping in a swooping arc. The tip clicked against the hand guard on Ryōichi’s sword hilt, and with a hefty push Ryōichi shoved his attacker away. Seeing an opening, one of Mitsuo’s companions rushed in from Ryōichi’s left, sword and arm outstretched. Stepping aside to dodge, Ryōichi followed up with a rapid slash. The outstretched arm flopped to the ground, detached from its owner.

arc. The tip clicked against the hand guard on Ryōichi’s sword hilt, and with a hefty push Ryōichi shoved his attacker away. Seeing an opening, one of Mitsuo’s companions rushed in from Ryōichi’s left, sword and arm outstretched. Stepping aside to dodge, Ryōichi followed up with a rapid slash. The outstretched arm flopped to the ground, detached from its owner.

Mitsuo attacked again, this time with more control, but again Ryōichi used his own weapon to deflect. At the last moment, he pulled his sword away, leaving Mitsuo to fall forward as all his strength went into cutting the air. Ryōichi rolled on his heels, nearly escaping the stab of Mitsuo’s second follower, who had snuck to his rear. The ambush had been aimed at the middle of Ryōichi’s back, but ended up leaving only a scratch. Pivoting, Ryōichi completed his spin with a two-handed thrust into the second follower’s stomach. Out of reflex, the stabbed man put his hands around the katana plunged into his gut, but succeeded only in slicing his hands as gravity pushed him off the blade and to the ground.

It was plain to see Mitsuo wavering after witnessing both of his friends so easily dispatched. His lips trembled and his knees wobbled. The steel he held between his fingers shook, like a weak root supporting a man on the edge of a cliff. Still, his arms and feet remained motionless. He was planted where he was, frozen in fear. He stared straight ahead, at the stranger and his weapon coated in blood. His two companions had been rendered useless in mere seconds. One was dead, the other flopping around like a fish out of water, clutching the stump where his arm had been. He waited for Ryōichi to come at him, but the bushy-haired samurai remained motionless, locked in a defensive stance.

Mitsuo raised his sword high one more time and ran, shouting curses at his enemy.

What happened next was a blur. When he regained his senses, he was panting, covered in sweat, every limb feeling like a porous sponge. He had swung his sword; he knew that, as his muscles ached from the power he had invested in the decisive blow. He took a deep breath, hurrying to recapture his composure—

The breath never came. It was then he realized that his throat had been cut open.

Gasping, he collapsed. All he could hear was the nauseating sound of him inhaling air, only for the air to be released again in the hole that had been made in his neck. All he could see was the bushy-haired samurai named Ryōichi walking into the shadows, not even looking back at the carnage left in his wake. Soon, Mituso’s hearing and his sight began to fade, lost in white noise and creeping blackness.

—

As predicted, Mitsuo had returned to the crossroads where he had slain Susumu and countless others before, just three nights after Ryōichi had been hired. Daisuke had stayed around long enough to watch the deed done before retreating to the rendezvous where Ryōichi would receive his payment. Daisuke leaned against the railing of the Kamo Bridge and watched the river running beneath, the sound of water calming his nerves. Although Ryōichi had been the one to do the killing tonight, Daisuke felt strangely ill at ease.

Half an hour passed before Ryōichi arrived. He looked a bit nervous, but still calm for a man who had just killed three men.

“I am sure the master will be pleased,” Daisuke said, his voice low. “And you too must take some pleasure that a beast like Hakkaku Mitsuo no longer sullies the word ‘samurai’ with his murder of innocent people. We suspected that someone like him would not last long against—”

Ryōichi waved a hand in the air, as if batting away the words before they reached his ears. “No need for flattery. Just pay up.”

Angered, Daisuke opened his mouth as if to say something more, but instead frowned and offered from within his kimono a pouch containing the 20 gold coins, as promised. With hardly a nod, Ryōichi scooped it up, placed it inside his own kimono and started to walk toward the other side of the bridge.

Daisuke opened his mouth again, hesitated, and then broke into a sprint after Ryōichi. He grabbed him by the shoulder and spun him around. “Wait!”

Annoyed, Ryōichi grimaced. “What is it?”

“I don’t understand you!” Daisuke protested. “Mitsuo was a disgrace to his class! He massacred people who did nothing wrong, solely because he was free to do so! You did an honorable thing tonight, and all you seem to care about is the money!”

Ryōichi chuckled. “A truly honorable samurai would never have betrayed his class and become a sword-for-hire, especially for someone like your master: a cutthroat merchant who pays others for their labor and then profits from it, never lifting a hand himself!”

“He wanted to avenge his son!”

“And he had the money to buy revenge,” Ryōichi replied. “Perhaps the loved ones of Mitsuo’s other victims will also rejoice at the news of his death, but in the end what I did tonight was so your master could feel better, not for the sake of something like ‘honor’ or ‘justice.’ Mitsuo may be dead, but someone just like him will be waiting at some crossroads tomorrow night, looking to kill a passerby with impunity. You shouldn’t think that one man or one act could stop the injustice that this world ignores and encourages.”

Daisuke shook his head. “You’re wrong!”

“Believe what you want. Where was ‘honor’ and ‘justice’ during the civil war, when vassals rebelled against their lords and took their place? The low overtook the high. Tokugawa Ieyasu may be on top now, but it was not so long ago he showed obeisance to someone else. Now that the time of war is over, there is no more use for warriors. Now it’s time for trading and prosperity, so merchants like your master and their vaults of wealth will be supreme. Once again, the low are overtaking the high. Samurai who cling to their privilege and the hope of glory won by the sword are living in the past. Boys like Hakkaku Mitsuo listen to the war stories of their fathers and grandfathers, thinking they too will someday become swordsmen, only to find that life denied to them. Just like it was denied to me, when I was cast out to beg and be spat upon, when it was only years ago I enjoyed endless praise for my bravery on the battlefield and devotion to swordsmanship.”

“I am praising you now,” Daisuke pointed out. “I’m telling you, you did a good thing.”

Ryōichi chortled. “Hakkaku Mitsuo committed tsujigiri a dozen or two dozen times. Meanwhile, a warlord like Tokugawa Ieyasu conscripts tens of thousands of peasants into his armies to fight and die to enrich him and his clan. If I killed him, maybe that would make a difference.” Perked up at the idea, he began to rub his chin. “Nah. That’d require too much work, and besides, some other bastard would just take his place.”

Daisuke, still dissatisfied, gazed down at his sandals.

Ryōichi placed a reassuring hand on Daisuke’s shoulder. “Times change and people have to change with them. Be content that you have a steady job, food in your belly, and a roof over your head.” With that, he turned and made once more for the other side of the bridge.

“If history has no more use for you,” Daisuke called, “then what will be your calling?”

“Don’t worry,” Ryōichi answered, smiling over his shoulder. “No matter how much things change, there will always be someone who wants someone else dead.”

END

Excellent story… thanks ☺